Sibylle Rauch: Munich as Her Stage

- Maximilian Von Stauffenberg

- 9 December 2025

- 0 Comments

Sibylle Rauch didn’t just act on stages in Munich-she made the city part of her performance. For over four decades, her presence shaped how audiences saw theater in Bavaria. You won’t find her name on tourist brochures, but if you’ve ever sat in the darkened stalls of the Münchner Kammerspiele or the Bayerisches Staatsschauspiel, you’ve felt her influence. She didn’t need spotlight tricks or viral moments. Her power came from silence, from the way she held a pause just long enough to make you lean forward.

Her First Breath on a Munich Stage

Rauch’s career began in the early 1980s, right after she graduated from the Munich Academy of Performing Arts. She wasn’t cast in a lead role at first. Her debut was a small part in a Brecht play at the Kammerspiele. The director, a stern man named Klaus Hager, told her after rehearsal: "You don’t shout. You don’t gesture. You just exist. That’s why people will watch you." That was the moment Munich became her stage-not because it was glamorous, but because it demanded truth. She spent the next ten years in ensemble roles, playing maids, neighbors, mothers, and widows. Each part was tiny, but she gave them weight. In a 1987 production of "The Good Person of Szechwan," she played a street vendor who never spoke a line. Yet, audiences remembered her-the way she wiped her hands on her apron, the way her eyes followed the main character like she knew a secret no one else did.

The Quiet Revolution

By the 1990s, German theater was shifting. Directors wanted more realism, less symbolism. Rauch thrived in that space. She didn’t chase fame. She chased precision. In 1993, she took on the role of Frau Kroll in Peter Handke’s "The Hour We Knew Nothing of Each Other." The script had no plot, no dialogue. Just 120 characters walking through a town square, doing ordinary things. Rauch played a woman who bought bread, sat on a bench, and stared at a pigeon for seven minutes straight. Critics called it "unbearably still." Audiences cried.

That performance changed everything. Suddenly, people started talking about her-not as a supporting actress, but as the soul of Munich theater. She didn’t give interviews. She didn’t post on social media. But when she walked into a rehearsal room, the energy shifted. Young actors would watch her, not to copy, but to learn how to be present.

What Made Her Different?

Most actors train to be heard. Rauch trained to be felt. She studied breathing patterns of elderly women in Munich’s English Garden. She spent afternoons in the Ostbahnhof train station, watching commuters who thought no one saw them. She recorded the way people adjusted their scarves when they were nervous, the way they looked away when someone asked a question they didn’t want to answer.

In 2001, she performed in a production of Chekhov’s "Three Sisters" where she played Olga, the eldest sister who gives up her dreams. In one scene, she sits alone at a table, folding laundry. The script says nothing about her hands. But Rauch’s hands told the whole story-how they moved slower each time, how the wrinkles in the fabric became more pronounced, how her fingers trembled just once before stopping completely. That moment lasted 47 seconds. No one clapped. But when the lights went out, you could hear people holding their breath.

Munich’s Unseen Theater

Munich isn’t Berlin. It’s not Paris. It doesn’t scream for attention. It waits. And Rauch learned to wait with it. She rarely performed outside Bavaria. When offered roles in Vienna or Zurich, she declined. "The air here is different," she once said in a rare 2005 interview with "Süddeutsche Zeitung." "It carries the weight of history, but it doesn’t force you to carry it. You can just be." That’s why her performances felt so real. She wasn’t pretending to be someone. She was letting the city speak through her.

Legacy in the Quiet Corners

She retired in 2019 after a final performance in "The Chairs" by Ionesco. She played the old woman who listens to invisible guests. The stage was empty except for a chair, a table, and her. She didn’t speak a word. She just smiled once, at nothing, and then closed her eyes. The audience sat in silence for 3 minutes and 14 seconds before the first person stood to clap.

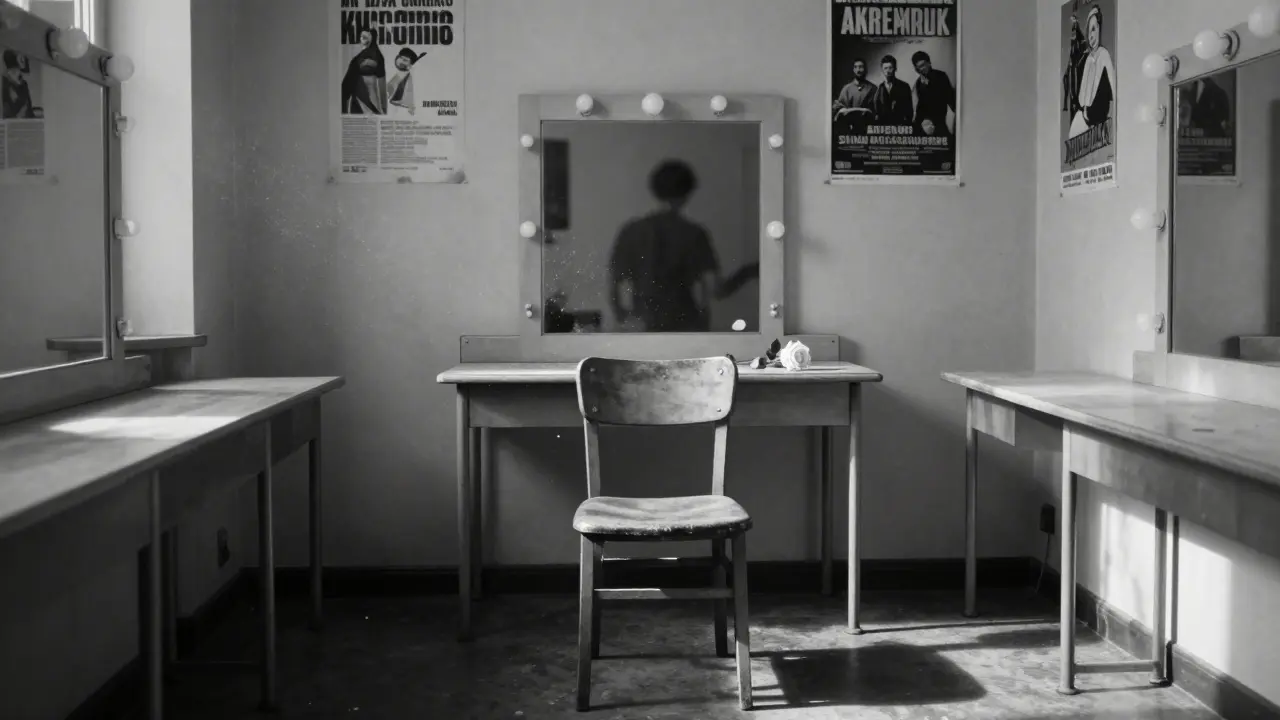

Now, her name is rarely mentioned in headlines. But if you ask the stage managers at the Münchner Kammerspiele, they’ll tell you about the way she always left a single rose on the dressing room table after every show. Or how she taught interns to sit in the audience before their own performances-to watch how people react when they think no one’s looking.

There’s no statue of her. No plaque. No Wikipedia page with a long biography. But if you go to the old rehearsal rooms behind the Staatsschauspiel, you’ll still find the same worn-out chair she used to sit in before curtain. And if you’re quiet enough, you might swear you can hear her breathing.

Why She Still Matters

In a world where every performance is recorded, shared, and judged in real time, Sibylle Rauch reminds us that some art doesn’t need an audience to be real. It only needs presence. She didn’t perform for likes. She performed because she believed in the quiet power of truth.

Her legacy isn’t in awards or reviews. It’s in the young actors who now sit in silence for three minutes before their scenes. In the directors who ask, "What’s she not saying?" instead of "What’s she saying?" In the way Munich’s theater still feels like a place where stories breathe, not just speak.

Who was Sibylle Rauch?

Sibylle Rauch was a German stage actress who spent over 40 years performing primarily in Munich theaters, including the Münchner Kammerspiele and Bayerisches Staatsschauspiel. Known for her subtle, deeply human performances, she became a quiet pillar of Bavarian theater without ever seeking fame or media attention.

Why is Munich important to her career?

Munich gave Rauch the space to develop her unique style-quiet, observant, and rooted in realism. Unlike larger theater hubs, Munich’s scene valued depth over spectacle, which allowed her to focus on small gestures and emotional truth. She rarely performed outside Bavaria, believing the city’s atmosphere shaped her art in ways no other place could.

Did Sibylle Rauch ever win major awards?

She received few formal awards, but that wasn’t her goal. In 2012, she was honored with the Bavarian Order of Merit for her contributions to theater culture, but she declined public ceremonies. Her recognition came from peers-actors, directors, and audiences who remembered her performances long after the curtain fell.

What made her acting style unique?

Rauch’s style was defined by stillness. She focused on micro-expressions, breathing patterns, and the weight of silence. She studied real people-commuters, shopkeepers, elderly women-to understand how emotion lives in the body when it’s not spoken. Her performances often had no big moments, yet left audiences deeply moved.

Where can I see her work today?

There are no official recordings of her performances, as she refused to be filmed on stage. However, some university archives in Munich hold audio recordings of her radio plays from the 1990s. Her influence lives on through the actors she mentored and the directors who still cite her as a model of understated performance.