How Munich Shaped Vivian Schmitt’s Career Path

- Maximilian Von Stauffenberg

- 13 December 2025

- 0 Comments

When people think of Munich, they picture Oktoberfest, neoclassical architecture, or BMW factories. But for Vivian Schmitt, the city was never about tourist spots or beer halls. It was the quiet corners of libraries, the echo of footsteps in empty galleries, and the late-night conversations in small cafés that changed everything. Munich didn’t just host her career-it rewired it.

First Impressions That Lasted

Schmitt moved to Munich in 2012, fresh out of a small university in Baden-Württemberg with a degree in art history and no clear plan. She didn’t come for fame. She came because the city’s public archives were open to anyone, and the state-funded arts grants were among the most generous in Germany. What she found wasn’t a glittering art scene-it was a system that rewarded patience, not talent alone.

She spent her first six months walking from the Pinakothek der Moderne to the Lenbachhaus, sketching in notebooks, taking notes on exhibition catalogs, and asking questions at the information desks. No one told her to do it. No one paid her. But the staff at the Kunsthalle started recognizing her face. By winter, they let her volunteer to help catalog 19th-century German lithographs. That unpaid job became her apprenticeship.

The Role of Public Funding

Munich’s cultural infrastructure isn’t built on private donors or celebrity patrons. It’s sustained by municipal budgets that prioritize access over exclusivity. In 2013, the city allocated €12 million to support emerging artists and researchers under 30. Schmitt applied for a grant to study the influence of Bavarian folk motifs on early modernist painters. Her proposal was rejected twice. The third time, she included handwritten transcriptions of letters from artists’ personal archives-documents no one else had bothered to digitize.

She got the grant. €8,500. Enough to rent a tiny studio near the Isar River and buy a secondhand scanner. She spent six months digitizing 347 unpublished letters from artists like Franz von Stuck and Hans Thoma. That archive later became the foundation of her first published paper, which was cited by three university departments in Germany and Austria.

Networking Without the Noise

Unlike Berlin or Hamburg, Munich doesn’t have a loud, party-driven art scene. There are no Instagram influencers selling “artist lifestyles.” Instead, connections happen over coffee at Café Luitpold, in the reading rooms of the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, or during the weekly curator meetups at the Städtische Galerie.

Schmitt didn’t chase gallerists. She showed up-every Tuesday-for the open forum where curators, archivists, and grad students discussed exhibition proposals. She didn’t speak much at first. But when she did, it was precise. She once corrected a senior curator on the provenance of a 1902 watercolor, citing a letter from the artist’s widow that had been archived in 1987 but never published. After that, people started asking her opinion.

The Turning Point: The Hidden Exhibition

In 2016, Schmitt proposed a small, unadvertised exhibition at the Munich City Museum. No press release. No social media. Just a single room titled “Unseen: Women Artists of the Bavarian Secession, 1892-1912.” She had spent two years tracking down works by women who had been excluded from official records-artists like Maria Caspar-Filser and Anna von Schaden. Many of the pieces had been stored in attic boxes, mislabeled as “family heirlooms.”

The show ran for three weeks. Only 427 people saw it. But one visitor was the director of the Albertina in Vienna. She invited Schmitt to co-curate a larger version. That exhibition traveled to four cities. Schmitt was 28. She hadn’t published a book. But she had built something no algorithm could replicate: trust through consistency.

Why Munich, and Not Another City?

Many assume that big cities like Paris or New York offer more opportunity. But Schmitt’s experience shows the opposite. In Munich, the bureaucracy was slow, but it was fair. The funding was limited, but it was transparent. The competition was quiet, but the standards were high.

She once told a journalist: “In Berlin, you need a viral video to get a grant. In Munich, you need a well-documented footnote.” That footnote became her reputation.

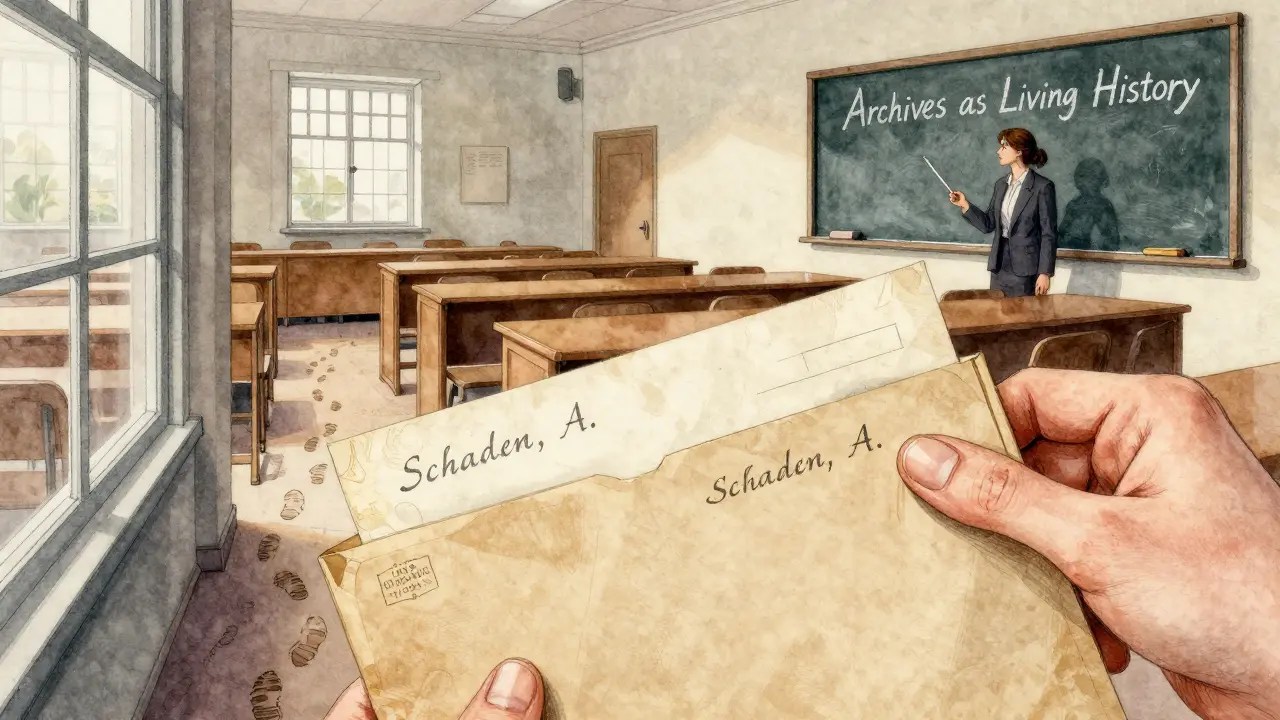

Today, Schmitt leads the Department of Modern German Art at the University of Munich. She teaches a course called “Archives as Living History.” Her students don’t just read about art-they visit storage rooms, handle fragile documents, and learn how to read handwriting from 1910. She insists on it. Because that’s how she learned.

What She Carried Away

Munich didn’t give Vivian Schmitt fame. It gave her tools. The discipline to dig through silence. The patience to wait for recognition. The understanding that real influence isn’t shouted-it’s quietly built, one archived letter, one corrected catalog entry, one small exhibition at a time.

She still walks past the same café on Herzog-Wilhelm-Straße. She doesn’t go in anymore. But she sometimes stops, looks at the window, and remembers the first time someone there handed her a cup of coffee and said, “You’re the one who found the Schaden letters, right?”

That was the moment she realized: Munich didn’t make her career. It showed her how to build one.

How did Munich’s cultural funding help Vivian Schmitt?

Munich offered transparent, publicly funded grants for young researchers under 30. Schmitt received €8,500 after submitting a detailed proposal with original archival material, which allowed her to digitize rare letters and launch her first published research.

What made Schmitt’s 2016 exhibition stand out?

It focused on overlooked female artists from the Bavarian Secession, using previously unarchived works stored in private collections. The exhibition had no marketing, yet caught the attention of a major museum director in Vienna due to its scholarly rigor and recovered history.

Why is Munich different from Berlin for emerging artists?

Berlin rewards visibility and social media presence. Munich rewards depth and documentation. Schmitt succeeded by building credibility through archival work, not by seeking attention. Recognition came from peers, not influencers.

Did Vivian Schmitt have formal mentors in Munich?

She didn’t have a single mentor. Instead, she learned from librarians, archivists, and curators who quietly allowed her access to restricted materials. Their trust, earned through consistent, respectful work, became her real guidance.

What is Vivian Schmitt teaching today?

She teaches “Archives as Living History” at the University of Munich, where students handle original documents, transcribe handwritten letters, and learn to verify provenance through physical archives-not just digital databases.