From Munich with Boldness: Annette Schwarz’s Journey

- Maximilian Von Stauffenberg

- 6 December 2025

- 0 Comments

Annette Schwarz didn’t set out to become a name in the art world. She just wanted to make something real. In a quiet corner of Munich, tucked between old brick buildings and the hum of trams, she started painting on scraps of wood she found in alleyways. No gallery wanted her work. No critic noticed her. But she kept going-not because she dreamed of fame, but because stopping felt like silence.

Starting With Nothing

In the early 2000s, Munich’s art scene was dominated by polished abstracts and expensive installations. Annette’s pieces were raw. She used rusted metal, torn fabric, and charcoal from burnt books. Her first solo show in 2007 was held in a disused laundromat on Schwanthalerstraße. Only 17 people showed up. Two bought something. One was a retired librarian. The other was a street musician who traded a handmade guitar for a small canvas titled “What the Rain Left Behind.”

She didn’t have a degree in fine arts. She never studied under a famous professor. Her only teacher was boredom-and the stubbornness that came with it. After her father died in 2003, she stopped waiting for permission to create. She started making art from what she had: old clothes, broken toys, the ashes of letters she never sent. Each piece became a quiet rebellion against the idea that art needed to be expensive to matter.

The Turning Point

In 2012, a curator from the Lenbachhaus stumbled into that laundromat show by accident. He was looking for a bathroom. Instead, he found a wall covered in textures that looked like memory itself. He didn’t buy anything that day. But he took photos. A month later, Annette got a letter asking if she’d consider a small room in the museum’s new “Unseen Voices” exhibition.

She said yes.

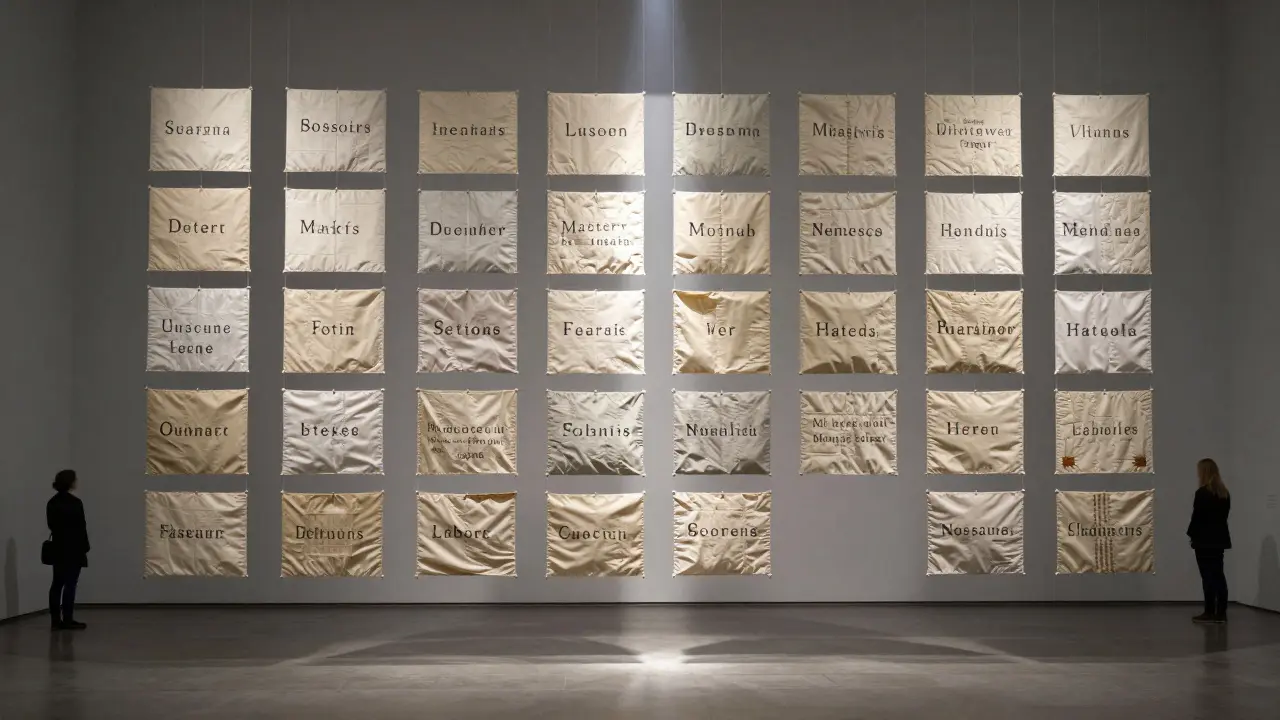

Her contribution? A 12-foot installation made of 347 hand-sewn fabric squares, each stitched with a single word from letters written by women in post-war Munich. The piece, “Silent Threads,” became the emotional center of the show. Visitors stood in front of it for minutes, sometimes hours. No labels. No explanations. Just fabric, thread, and silence.

After that, things changed-not fast, but deeply. Galleries started calling. Collectors asked for commissions. But Annette didn’t move to Berlin. She didn’t hire an agent. She kept her studio in the same neighborhood, now a converted bicycle repair shop with peeling green paint and a broken doorbell.

What Makes Her Work Different

Annette’s art doesn’t shout. It waits. It breathes. You have to lean in to hear it.

Unlike many contemporary artists who rely on digital tools or mass-produced materials, she works almost entirely with found objects. Her palette comes from decay: faded wallpaper, cracked porcelain, rusted keys. She doesn’t paint over mistakes. She builds around them. One piece, “The Chair That Sat Alone,” is made from the broken legs of a 1950s dining chair, wrapped in yarn knitted from sweaters donated by strangers. Each strand carries a note: “I miss my mother,” “I left too soon,” “I didn’t know how to say goodbye.”

Her process is slow. A single piece can take months. She doesn’t sketch. She doesn’t plan. She lets the materials guide her. “The wood remembers,” she once said in an interview. “It knows what it was before it became trash. I just help it speak.”

This approach has drawn comparisons to Joseph Beuys-but Annette rejects the label. “Beuys was a philosopher. I’m just someone who picks things up off the ground.”

Her Influence on Munich’s Art Scene

Today, Munich’s underground art scene is full of young creators who cite Annette as their quiet inspiration. Not because she’s famous, but because she proved you don’t need permission to belong.

She started a free workshop in 2015 called “Found Things, Found Voices.” It meets every Thursday at her studio. No fees. No applications. Just a table, some glue, and a pile of discarded objects. Over 1,200 people have come through-students, retirees, refugees, factory workers. Many never made art before. Now, some have shown in local galleries.

She doesn’t teach technique. She teaches attention. “Look at the crack in the cup,” she tells them. “Not as damage. As history.”

Her influence is subtle but real. In 2023, the city of Munich launched a public art initiative called “Reclaim the Ordinary.” It funds small, community-based installations using recycled materials. The program’s lead architect admitted: “We were inspired by Annette’s work. Not her style-her courage.”

Why Boldness Isn’t Loud

Boldness isn’t about volume. It’s about persistence. It’s about showing up when no one’s watching. It’s about choosing to create when the world says, “Why bother?”

Annette Schwarz never wanted to be a symbol. But she became one anyway-not because she chased it, but because she refused to let go of what mattered to her.

Her studio still has the same broken doorbell. The same stack of unsold canvases in the corner. The same cup of cold tea on the windowsill. Visitors sometimes ask if she’s ever thought about selling out. She smiles and points to the wall.

There, hanging crookedly, is a small piece made from a child’s broken toy train. One wheel is missing. The paint is peeling. And underneath, in faded ink, it says: “I still go places.”

Her Legacy Isn’t in Galleries

Annette’s legacy isn’t in auction records or museum acquisitions. It’s in the 14-year-old girl who showed up at her studio last month with a jar of buttons and said, “I don’t know how to make anything. But I want to try.”

It’s in the retired nurse who now turns hospital gowns into quilts and calls them “Stories of Sleep.”

It’s in the Syrian refugee who stitched his grandmother’s embroidery into a mural of the Aleppo skyline-and hung it on the wall of a community center, where it still draws tears.

She never gave a TED Talk. Never appeared on a podcast. Never sold a print online. But her work lives in the quiet spaces where people feel seen.

That’s the kind of boldness that lasts.

Who is Annette Schwarz?

Annette Schwarz is a Munich-based artist known for her raw, found-object installations that transform discarded materials into emotional narratives. She has no formal art training and built her career through quiet persistence, starting in a disused laundromat and eventually gaining recognition from institutions like the Lenbachhaus. Her work centers on memory, loss, and resilience.

What materials does Annette Schwarz use in her art?

She uses only found and discarded items: rusted metal, torn fabric, broken toys, old clothing, burnt books, cracked porcelain, and handwritten letters. She avoids new or mass-produced materials, believing that history lives in decay. Each object carries a story she helps reveal through arrangement and texture.

Where can I see Annette Schwarz’s art?

Her work has been exhibited at the Lenbachhaus in Munich and several smaller galleries across Germany. Most of her pieces remain in private collections or are part of community installations. She does not sell prints or online reproductions. The only consistent public space to experience her influence is her studio workshop, which is open to visitors every Thursday.

Did Annette Schwarz ever gain commercial success?

She has never sought commercial success. While collectors have purchased her work, she refuses to increase prices or mass-produce pieces. She turned down a major international gallery offer in 2018, saying, “If my art needs a price tag to be seen, then it’s already lost.” Her value lies in accessibility, not profit.

What is the “Found Things, Found Voices” workshop?

Started in 2015, it’s a free, weekly art session hosted in Annette’s studio where anyone can come to create with discarded objects. No experience needed. No fees. No rules. Over 1,200 people have participated, many of whom have gone on to exhibit their own work. The workshop is her way of spreading the belief that creativity doesn’t require permission.